A little delayed, but WordPress was giving me some problems last week, so here it is!.

Last weekend was our first totally free weekend since the beginning of September. As soon as the last class ended last week (or at least the last one we were going to) the Furmanites of Madrid dispersed for the far corners of Europe. Some went to Vienna. Some went to Dublin. I, however, ventured to the heart of Deutschland, to the great walled city where JFK so infamously gaffed his potentially powerful statement of brotherhood, “I am a Berliner.”

At first, I wasn’t sure what to expect. With my limited knowledge of the post-war Germany and almost nonexistent knowledge of Berlin, I pictured it as a kind of sad, gray city. Pretty much your typical German urban powerhouse. As it turns out, I couldn’t have been more wrong. East Berlin, having essentially been completely rebuilt in the past few decades is thriving with life. Gone are the days of no-man’s-land and utter hell. Now, East Berlin – where we spent pretty much all of our time – is full of shops (from local quirky to 90-euros-for-a-tshirt designer), restaurants, clubs, currywurst stands, bars, and whatever else you could possibly want. The walkway by the river Spree is lined with flea markets and trees (which happened to be changing color while were there), with old, ivy-covered German buildings watching over passerby. Mitte, the central neighborhood where our apartment was is now the up and coming neighborhood for all of Berlin. Naturally, we couldn’t see all of the city (which is apparently 9 times the size of Paris when you include suburban areas), but what we did see was amazing.

Having been to more museums and sat through more tours than I can count here in Spain, we kept things of that nature to a minimum.That said, we couldn’t be in a city with an island dedicated to museums without going to at least one. The Pergamon Museum, for example, houses a collection of “classical antiquities” (basically archeological things from like the 7th century B.C) and a sizable collection of Islamic art and architecture. The DDR Museum, while not technically on the island, housed a very different kind of exhibition. Full of memorabilia and history from pre-Mauerfall Berlin, the DDR is actually a hands on museum, where you can try on era clothing, lounge on the couch in a typical Deutsche Demokratische Republik (Communist half of Berlin) living room, or try out the bed in your everyday communist jail cell. It dealt with pretty much every aspect of every day life back then, which was really interesting for someone as Berlin ignorant as I was.

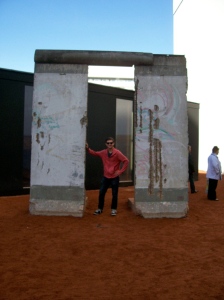

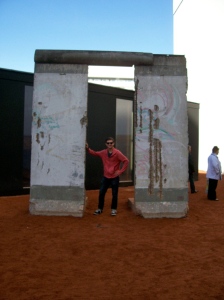

But no trip to Berlin would be complete without seeing the wall, to which we devoted almost an entire day. We started off at Checkpoint Charlie, the American security checkpoint between East and West Berlin, and the adjacent wall museum, where we expected to see the murals that fill almost every Google Image search of Berlin. But no dice. Not yet willing to give up, we followed the bricks marking where the wall once stood throughout Berlin. We passed Brandenburg Gate, the Topography of Terror museum, the Memorial to Murdered Jews, and the imposing (and oh so German) Reichstag. Eventually, we realized we had been going in almost the complete wrong direction, so we hopped on the U-bahn and headed south east to the East Gallery, a mile-long section of the wall dedicated to unification and decorated with vibrant murals. Recently, however, the city commissioned a mural renovation project, and some of the restoring artists took some pretty severe artistic liberties with the original murals. Even still it was an impressive site.

But no trip to Berlin would be complete without seeing the wall, to which we devoted almost an entire day. We started off at Checkpoint Charlie, the American security checkpoint between East and West Berlin, and the adjacent wall museum, where we expected to see the murals that fill almost every Google Image search of Berlin. But no dice. Not yet willing to give up, we followed the bricks marking where the wall once stood throughout Berlin. We passed Brandenburg Gate, the Topography of Terror museum, the Memorial to Murdered Jews, and the imposing (and oh so German) Reichstag. Eventually, we realized we had been going in almost the complete wrong direction, so we hopped on the U-bahn and headed south east to the East Gallery, a mile-long section of the wall dedicated to unification and decorated with vibrant murals. Recently, however, the city commissioned a mural renovation project, and some of the restoring artists took some pretty severe artistic liberties with the original murals. Even still it was an impressive site.

I know it sounds like we mostly just walked around and looked at stuff (which is true) but what would a visit to Berlin be without a venture into its nightlife, whose reputation had far preceded itself. One night, we found our way to what appeared to be an old brewery complex that had been converted into some kind of entertainment plaza with a few clubs and restaurants. The biggest club was unfortunately reserved for a wedding party or something, but we managed to find another, much smaller club/bar thing that didn’t seem all bad. At first they were playing old American rap with throwbacks to Will Smith, Fifty Cent, Jay Z, and the likes. But after about 30 minutes everything changed drastically. I first realized something was up when the oh-so-loveable intro to Limp Bizkit’s 90s hit “Rollin” (can you hear my tongue in my cheek?) trickled from the speakers. This masterpiece was followed by a mixture of Trapt, Stained, and whatever other hard rock band you can think of. It wasn’t so bad at first because at least we knew the words and could playfully sing along. But it didn’t stop there. Before long the German rock made its obviously long anticipated debut. We had no idea what was going on, but everyone seemed to love the gibberish songs that alternated between slow, sensual breakdowns to Irish jig like choruses. Needless to say it was an experience.

The next night went a little bit better. We found a nightclub online that consistently made all of the top club lists in Berlin, and for good reason. Situated on the thirteenth floor of an office building, Weekend is surrounded by giant plate-glass windows that afford panoramic views of the entire city – perfect for catching the sunrise after a long night of partying. The comfy leather couches and powerful sound system make for a great party setting. Unfortunately, fashion in Berlin changes at a Zoolander pace, and it seemed as though Weekend had run its course. Maybe it was just a bad night, but the club never really filled up and the dj played the same house beat the entire time we were there. By about 4 everyone started filling out, and we decided it was probably high time to walk home. It was still a lot of fun though.

All in all, Berlin was an amazing city, but it was one of the hardest trips I’ve made. In Madrid, we can understand what people are asking us, read the signs telling us where to go, and actually have some idea what we’re ordering in restaurants. When I was in France last summer, it was at least close enough to Spanish that I could more or less understand the simple things (with extensive help of a travel dictionary). But German is a different story. Even thought it’s basically the sister language to English, I could hardly understand anything. The similarities are much more obvious when you can hear the word spoken out loud, but when people spoke to us I had no hope of picking out individual words. On our part, communicating involved a lot of pointing, nodding, and indistinct grunting. It was the first time I had been somewhere where I literally knew nothing about the language, culture, or city. But that’s what I loved about it. The groups that went to Dublin raved about how nice it was to hear English for a change and about how they were able to meet so many people without a language barrier. For me, the adventure of being completely immersed and completely lost is half the fun. Finding our own way around the city, decoding signs and menus, and trying to understand the guy who sold us four subway receipts instead of tickets are things I will never forget. It just amazes me how much variation there can be between cultures.

That said, I was grateful to return to Madrid. Not knowing any of the language – except the curses our cab driver taught us – made me realize how much Spanish I actually knew and appreciate the fact that I could understand what was going on in Madrid. When I climbed the stairs out of Francos Rodríguez, it felt as though I were returning home. It was a strange, yet oddly satisfying feeling.